Question

In: Physics

Research and explain in more detail than given in the lecture pages how a Molecular switch...

Research and explain in more detail than given in the lecture pages how a Molecular switch works and what the prospects are for building a molecular computer that makes use of these switches.

Solutions

Expert Solution

A molecular switch is a molecule that can be reversibly shifted between two or more stable states.[1] The molecules may be shifted between the states in response to environmental stimuli, such as changes in pH, light, temperature, an electrical current, microenvironment, or in the presence of a ligand. In some cases, a combination of stimuli is required. The oldest forms of synthetic molecular switches are pH indicators, which display distinct colors as a function of pH. Currently synthetic molecular switches are of interest in the field of nanotechnology for application inmolecular computers. Molecular switches are also important to in biology because many biological functions are based on it, for instance allosteric regulation and vision. They are also one of the simplest examples of molecular machines.

A widely studied class are photochromic compounds which are able to switch between electronic configurations when irradiated by light of a specific wavelength. Each state has a specific absorption maximum which can then be read out by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Members of this class include azobenzenes, diarylethenes, dithienylethenes, fulgides, stilbenes, spiropyrans and phenoxynaphthacene quinones.

Chiroptical molecular switches are a specific subgroup with photochemical switching taking place between an enantiomeric pairs. In these compounds the readout is by circular dichroism rather than by ordinary spectroscopy. [2] Hindered alkenes such as the one depicted below change their helicity (see: planar chirality) as response to irradiation with right or left-handed circularly polarized light

Chiroptical molecular switches that show directional motion are considered synthetic molecular motors:[3]

-

-

In host-guest chemistry the bistable states of molecular switches differ in their affinity for guests. Many early examples of such systems are based on crown ether chemistry. The first switchable host is described in 1978 by Desvergne & Bouas-Laurent[4][5] who create a crown ether via photochemical anthracene dimerization. Although not strictly speaking switchable the compound is able to take up cations after a photochemical trigger and exposure to acetonitrile gives back the open form.

In 1980 Yamashita et al.[6] construct a crown ether already incorporating the anthracene units (an anthracenophane) and also study ion uptake vs photochemistry.

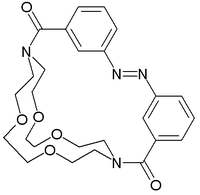

Also in 1980 Shinkai throws out the anthracene unit as photoantenna in favor of an azobenzene moiety[7] and for the first time envisions the existence of molecules with an on-off switch. In this molecule light triggers a trans-cis isomerization of the azo group which results in ring expansion. Thus in the trans form the crown binds preferentially to ammonium, lithium and sodium ions while in the cis form the preference is for potassium and rubidium (both larger ions in same alkali metal group). In the dark the reverse isomerization takes place.

Shinkai employs this devices in actual ion transport mimicking the biochemical action of monensin and nigericin:[8][9] in a biphasic system ions are taken up triggered by light in one phase and deposited in the other phase in absence of light.

-

Mechanically-interlocked molecular switches[edit]

Some of the most advanced molecular switches are based on mechanically-interlocked molecular architectures where the bistable states differ in the position of the macrocycle. In 1991Stoddart[10] devices a molecular shuttle based on a rotaxane on which a molecular bead is able to shuttle between two docking stations situated on a molecular thread. Stoddart predicts that when the stations are dissimilar with each of the stations addressed by a different external stimulus the shuttle becomes a molecular machine. In 1993 Stoddart is scooped by supramolecular chemistry pioneer Fritz V

Related Solutions

Describe with detail how this molecular switch is analogous to a light switch that one person turns on and another person turns off.

Explain in detail how glass transition temperature and molecular mobilityrelate to the following: a.) a stable...

Explain in detail how glass transition temperature and molecular mobility relate to the following: a. A...

In not less than 50 pages, discuss with examples and in sufficient detail, the economic and...

Define and Explain "Group Dynamics". 400 words at least and not more than 2 pages. (submit...

Submit a paper which is 2-3 pages in length (no more than 4-pages), exclusive of the...

Submit a paper which is 2-3 pages in length (no more than 3-pages), exclusive of the...

Submit a paper which is 2-3 pages in length (no more than 3-pages), exclusive of the...

Please explain the following bio-molecular tools in detail

Submit a written paper which is 3-4 pages in length (no more than 4-pages), exclusive of...

- Answer correctly the below 25 multiple questions on Software Development Security. Please I will appreciate the...

- 1. The activation energy of a certain reaction is 41.5kJ/mol . At 20 ?C , the...

- Give TWO pieces of evidence that you've successfully made methyl salicylate. Remember when you cite TLC...

- Describe briefly the evolution of Craniata and Vertebrata.

- How many grams are in a 0.10 mol sample of ethyl alcohol?

- For this assignment you will write a program with multiple functions that will generate and save...

- How many grays is this?Part A A dose of 4.7 Sv of γ rays in a...

genius_generous answered 2 years ago

genius_generous answered 2 years ago